The latest in a series of articles in which people involved with the Rye Castle Museum choose an object from the collection that represents an aspect of the history of the town and its environs and tell us what it means to them.

The Smugglers’ Lantern

This month’s museum object is the 18th century smugglers’ signalling lamp displayed in Ypres Tower, chosen by museum treasurer, Sheila Maddock. The light container was held in the crook of the left arm while the right hand, placed over the end of the light-emitting spout, signalled the message. The single candle’s light inside the lantern could be seen as a pinpoint of light well out to sea.

Sheila Maddock writes:

“Everyone likes tales of smuggling, particularly children, and those visiting the Ypres Tower either as a school party or with their parents are no exception. Rye, like many coastal towns was a centre for smuggling over the centuries, but particularly in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The smugglers on the land would watch to see which beach was clear of Revenue Men and signal to the ship at sea to indicate where to land. The smugglers needed to avoid the officers on spotting their light, and one solution was to use a lantern with a long spout in front, which meant the light only shone out to sea.

“A message could be signalled by putting a hand over the end of the spout. We are lucky enough to have such a lantern in the Ypres Tower, which was found in a hidden room in Iden, and it proved so popular with school parties, that we had a replica made for children to handle. This was enjoyed by the children, but it did raise questions as to how the smugglers used it. I experimented using a candle, but the lantern soon became burning hot, so demonstrations had to be made using a torch. Perhaps the smugglers placed the lantern on a rock, or they had very thick clothing.

“It is exciting to think that our lantern may have once shone out to sea along the local coast guiding in the smugglers’ ships, although perhaps we would rather not think too much about the very bloodthirsty and violent ways in which the smugglers treated their enemies.”

Early smuggling

Romney Marsh’s fertile land, reclaimed from the sea, has always been a prime location for raising sheep whose wool was highly-prized both at home and abroad.

Smuggling is known to have existed in the Rye area since the 13th century when Edward I introduced the customs system which imposed a tax of £3 per bag, rising to £6, on wool being exported abroad. The earliest references to smuggling are a warrant in 1301 to search for wool, hides, bales and all other merchandise and persons attempting to export money or silver.

In 1357 an Admiralty inquest was held at Rye before the deputy lord warden of the Cinque Ports to collect evidence against Simon Portier and several other men for exporting uncustomed wool from the port of Pevensey.

From the late 1550s smuggling became much more worthwhile with the introduction of a revised customs tariff and a new series of impositions. Further restrictions on trade, by customs and excise duties, introduced in the 17th century, made many common utilities such as candles and beer very expensive.

The expansion of smuggling

By the end of the 17th century, social conditions encouraged the expansion of smuggling into a widespread occupation affecting many of the residents of Kent and Sussex. Living conditions became harder, unemployment increased, and smuggling offered an alternative to poverty.

Many smugglers wore a bee-skep, in which eye and mouth-holes had been cut. Such a disguise was an offence, so much so that anyone having his face blackened, masked or otherwise disguised when smuggling contraband goods could be adjudged of felony and sentenced to death.

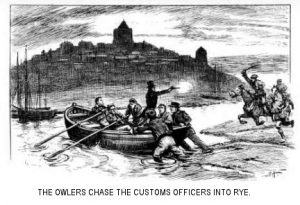

Restrictions on the export of English wool imposed to protect the cloth industry, first in 1614 and subsequently increased by the late 17th century, had made wool smuggling into a major trade. This was known locally as the owling trade and the wool smugglers were known as owlers, as they worked at night, often using the hoot of an owl as a signal. The coastal areas around Rye where the wool was produced were so near to France that even the threat of death was no great deterrent.

The owling trade expanded into the import of luxury goods from the continent. Silks, tea, tobacco and brandy were profitable items to bring in to evade the heavy duties imposed by the government.

Smugglers became large, highly organised and heavily armed groups, based either in convenient landing places on the coast, like Rye, Hastings, Pevensey and Bexhill or strategically placed villages on the roads to London and the interior, like Brede and Bamber. Long before the end of the 17th century, import smuggling was so great that the government was in danger of losing control of the situation. The most notorious smuggling area of the 18th century was the East Kent coast and Romney Marsh in particular.

Combatting smuggling

By 1700 riding officers were appointed, stationed along the coast to control the illegal export of wool. An officer had to provide his own horse to patrol an area of coast at night. He was paid £25 a year plus an allowance for his horse. His job was to listen to rumours, keep a low profile and write a daily record of all he saw. It was not a popular service but continued until after 1850.

Other preventive services trying to outwit the smugglers were Customs House officers, responsible for legal trade, and excise officers, whose duty was to collect taxes on manufactured goods later extended to various other imported goods. Each port had a Customs House collector supported by other officers ranging from his deputy down to boatmen. In 1822 there were 28 such officers in Rye alone, which gives an idea of the scale of the smuggling enterprise.

In addition to the land-based officers there was a small fleet of Revenue vessels, cutters and luggers, used to patrol the sea. They were too few to be really effective against larger smuggling boats.

Boatbuilders of Rye were especially adept at devising secret compartments to outwit Customs officers when they rummaged cargo. Many of the medieval churches on the marsh were used to store contraband or as places to hide. These include the remote and isolated Fairfield, as well as churches in Brookland, Ivychurch and Snargate. In Rye itself, a tunnel leads from the Mermaid Inn to the Old Bell, useful for a quick escape. Many ways were found to hide goods or people including adapting furniture so that there were hidden spaces within it, cupboards were made that could swivel to get to hidden stairs behind, and in many houses. all the attics ran into one so people could quickly escape detection by running from one house to another.

The notorious Hawkhurst gang

From the 18th century to the early 19th century there were many smugglers in the Rye area. The most notorious and formidable gang was the Hawkhurst Gang. They used the Mermaid Inn in Mermaid Street, as one of their bases terrorising the area of Kent and Sussex and no one dared to interfere with their activities. Its members did not hesitate to torture or murder anyone who opposed their operations.

The gang was finally defeated in 1747 by the Goudhurst Militia and its members executed in 1749. Rye smugglers were very successful in evading the law since there is little evidence of their being brought to trial. However, the Ypres Tower, used as a prison, is known to have housed smugglers.

Coastguards, customs reforms and the decline of smuggling

In 1821 the National Coastguard Service was introduced. This evolved into a disciplined and uniformed body, with shore-based patrols, a rowing guard offshore and men on the Revenue cutters patrolling the sea. Coastguard cottages were built at regular points round the coast to house the officers. In the war against smuggling the initiative had passed from the smuggler.

The most important factor in the suppression of smuggling was the enormous reduction and abolition of most of the duties as part of the policy of free trade in the first half of the 19th century. With the wholesale reform of the Customs service in 1853, which ensured a loyal and efficient force, the picture is completed. Smuggling, thereafter, was relatively unimportant. The coastguards remained, but their work became more of a sea rescue and life-saving service.

The exploits of the smugglers have inspired many writers, most notably the Dr Syn novels by Russell Thorndike, whose central character is a vicar by day and a ruthless leader of smugglers by night.

Rye Museum has two sites, one in a former bottling factory in East Street and the other at the Castle / Ypres Tower.

Castle / Ypres Tower is open daily throughout the year. March 30 to October 31 from 10:30am to 5pm. November 1 to March 29 from 10:30am to 3:30pm.

East Street is open at weekends from April to October from 10:30am to 4:30pm (subject to availability of volunteers).

Image Credits: Rye Castle Museum , The Project Gutenberg, The Smugglers, by Charles G. Harper, Illustrated by Paul Hardy , Nick Forman .

What a brilliant object. I think I know the house it came from, bcs I believe the attic window in which it sat is still visible. Strangely, I first heard about this lamp sitting with a colleague a long way away in Gray’s Inn Rd in London. He said, after asking where I lived, ‘Oh, my Grandparents are from near Rye…’ He described a signal lamp that had been discovered in their house and donated to the Museum. How strange to finally see it! Rye’s legends travel far and wide, it seems. Both of our museums are brilliant. The collection of Sussex pottery at East St is worth the visit itself.

The smugglers lamp was found by my Grandfather Alfred Martin in a secret

room at his house in Grove Lane Iden

also many other artefacts were found in

the underground tunnel beneath his

house . I am thinking of writing a

booklet as so much history there . Jude