This is the next in a series of articles in which people involved with the Rye Castle Museum choose an object from the collection which represents an aspect of the history of the town, and its environs, and tell us what it means to them.

The Tudor castle door

Displayed in one of the cells in the Rye Castle / Ypres Tower is a Tudor door which was originally situated at the bottom of the spiral staircase, to the left of the current entrance door. It had been installed in around 1552, at the same time as a new roof and new floors, which cost the corporation £5, and replaced the original medieval door which was centrally placed on the northern side of the castle.

In 2008, when other major restorative work aiming to stop serious water penetration was carried out at the castle, including putting on a new roof, the decision was made to close up the door at the foot of the stairs and re-open the previous central door. The original slots for the portcullis were found to be still in situ there.

Jo Kirkham, chair of Rye Castle Museum says: “The door leaned forlornly against the wall in the Medieval herb garden after being removed as the castle’s main door in 2008. What could we do with it? Then the carpenter working on the new study room / library at East Street in 2018 / 19 saw it one day and was really excited, immediately offering to ‘conserve it’ for us just for the cost of materials – mainly for new handmade ‘medieval’ nails. I was thrilled to accept his offer – and it has taken Martin nearly three years to get it to a stable state with which he is satisfied. I think it looks amazing and I really enjoyed researching how former Ryer’s made such doors and the reasons behind their decisions. They did a fantastic job as it has survived being exposed to the weather for almost 500 years!”

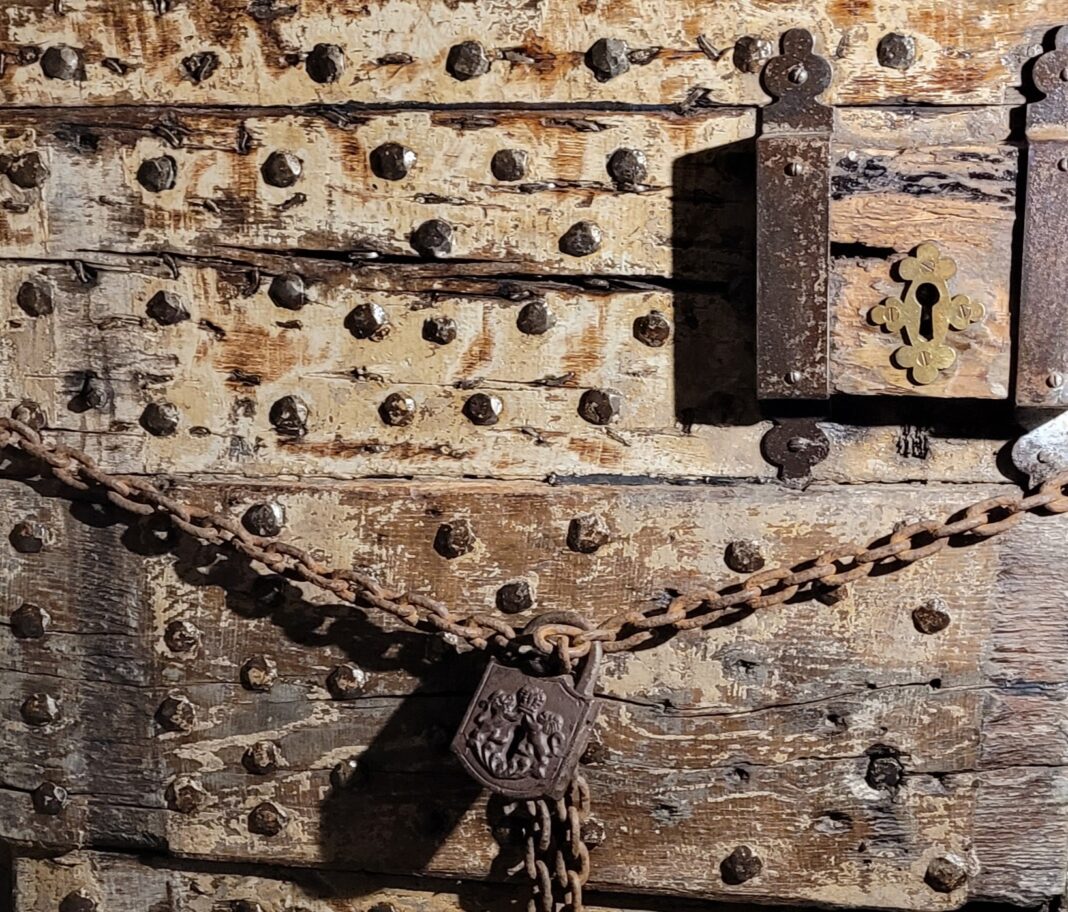

The door is made of aged and cured oak which made it very hard and resistant to fire. It has vertical planks on the outside and horizontal ones on the inside, all held with large hand-forged nails which penetrate both layers and which are bent over at the end, with the heads appearing to be studs on the outside.

Extra iron bars strengthened it on the rear as did two large iron brackets near the top and bottom of the door which allowed the door to be fixed to the jamb with two movable thick iron bars, which could be dropped through an iron ring, each held ready for use on a chain in emergency. The iron work was usually made by local blacksmiths.

With its thick double layer planks and iron bars and studs, the door would resist attacks by axe and sword, hopefully the incoming blades being broken off.

The door used a solid key, and the lock permitted access from both sides of the door, so the same key could lock in or out.

The conserved door is a welcome addition to the museum’s exhibits and its construction demonstrates how our ancestors thought about, and then constructed, what was an important element of the town’s defence. Many other very old rare doors can be seen in situ inside the building.

Rye Castle / Ypres Tower History

Ypres Tower, also known as Rye Castle, is a three-storey square building with round towers built on each corner, a Medieval herb garden and a further tower housing the women’s accommodation, known as the ‘Women’s Tower’.

It is uncertain as to when the first castle was built in Rye, but documents have come to light recently which describe when Louis, the son of the French King Louis VIII, who had invaded England in 1216 to fight King John, entered Rye Castle and took all the stores held there.

On the orders of Henry III around 1249, money was found to strengthen Rye Castle and, in the 1300s and 1400s, during the Hundred Years War with France, it played an important role in defending the town, surviving the fire which had destroyed almost all of Rye except the few stone buildings, in 1377.

In 1430, when the wars seemed to be now mainly on the continent, and Rye desperately needed money to rebuild the town after the fire, the castle became the home of John de Iprys (the name Ypres comes from him and not, as many assume from the famous first world war battle of that name). It kept the rights to use it for defence in time of attack, and from the 1470s prisoners were held there, and it continued to be used as a prison until 1890s, when a new police station, with its own cells was built in Church Square. From then until 1959 the castle basement was used as a mortuary while the Rye Castle Museum opened in 1954, using the rest of the building.

The Prison

It is known that there was a prison in Rye in 1256 / 57, as two couples were held there awaiting trial for murder.

For 400 years the castle/ Badding’s / Ypres Tower served as the town jail, housing vagabonds, vagrants, debtors, army deserters, murderers, ‘witches’, smuggler’s, pressed men (those taken by force for the navy or army), and those awaiting execution. Penalties included being hanged, burnt at the stake (rare), whipped or fined. Later came transportation to penal colonies, such as Australia. The south-west cell is reputed as having been padded for violent or disturbed prisoners.

Men, women and children were locked up together in the turret chambers. Conditions were harsh: prisoners slept on the floor which was covered in straw and was filthy as there were no toilet facilities; they were restrained with leg and body irons; and they had very little to eat, bread, beer and water being the only sustenance. There was little in the way of activities to pass the time.

Prison reformers such as Elizabeth Fry believed that prisons should have basic welfare standards and offer prisoners education and religious instruction. She came to Rye in 1835 and, after seeing the conditions in the castle, encouraged the corporation to build separate cells for women. The Women’s Tower was completed in 1837 with beds and a fireplace. Conditions were still hard, and prisoners had to take part in long hours of work such as oakum picking (unpicking old ropes) or sewing sacks. They also had to clean their cells and take part in an hour’s exercise in the yard, walking in silence.

In 1865, the gaol was downgraded to a lock-up.

Ypres Tower today

Since 1954, Ypres Tower has housed the Rye Castle Museum, open to the public daily.

There can be seen, the cells where prisoners were chained, as well as where the murderer John Breads was incarcerated before he was hung and his body left in a gibbet on the marsh (a replica of the gibbet and replica skeleton can be seen in the museum, John Breads’s skull and the original gibbet being in the town hall). There are displays on medieval warfare, smuggling, shipbuilding, the Cinque Ports Volunteers, and other aspects of the history of the town. As well as a model showing the changes to the Romney Marsh coastline and the defences against Napoleon, there is a balcony with extensive views across of the river Rother and across the Marsh.

The castle is a scheduled ancient monument and a grade 1 listed building which has required major restoration over the years and continues to need regular maintenance. The museum is almost completely self-funding and receives no government or council funding to maintain the historical building and is mostly run by a dedicated team of volunteers.

Rye Castle Museum has two sites, one is the Castle / Ypres Tower and the other in a former bottling factory at 3 East Street, which houses many of our local history exhibits.

Castle / Ypres Tower is open daily throughout the year. March 30 to October 31 from 10:30am to 5pm. November 1 to March 29 from 10:30am to 3:30pm.

East Street is open at weekends from April to October from 10:30am to 4:30pm (subject to availability of volunteers).

Image Credits: Juliet Duff , Rye Castle Museum , Nick Forman .

what a great article, just about everything that interests me about our ancient towns history