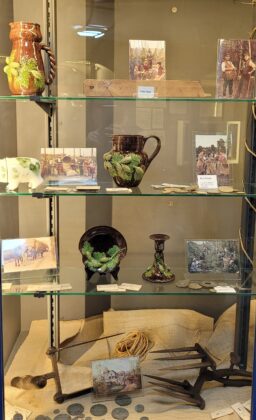

This month’s museum object is the pair of hop-farmers stilts on display in the covered walkway to Rye Castle Museum at 3 East Street, chosen by museum volunteer, Sally Masters.

The earliest reference to hops was in the 6th century BC when Pliny described the hairy-stemmed vine that grew amongst hedges and trees as “the wolf of the willow” as the hop was as destructive as a wolf amongst sheep. In the 7th to 9th century there are records of monastic hop gardens in France and Germany used for flavouring and medicinal purposes, and later in 13th and 14th century hops were used in beer in Germany, Flanders and the Netherlands.

Traditionally, English ale did not use hops but beer known as “treated ale”, made with hops, arrived in Winchelsea in around 1400, mainly for Dutchmen working in the area. Henry VIII forbade the use of hops but by the mid 16th century beer made with hops was widely produced, with hop farms established in Kent and East Sussex. In 1524 a licence was granted to Sir Edward Guildford to export hops and there are records of a Hoppe-House in Rye in 1585. The rapid growth of hop growing even led to a protectionist act in 1603 to control imports of hops from abroad. This area was particularly good for hop farming: the soil was good; there was plenty of wood for the hop poles and to make charcoal for the drying kilns; farms had enclosed fields; and prosperous farmers had the wealth to invest in the setting up of the hop fields.

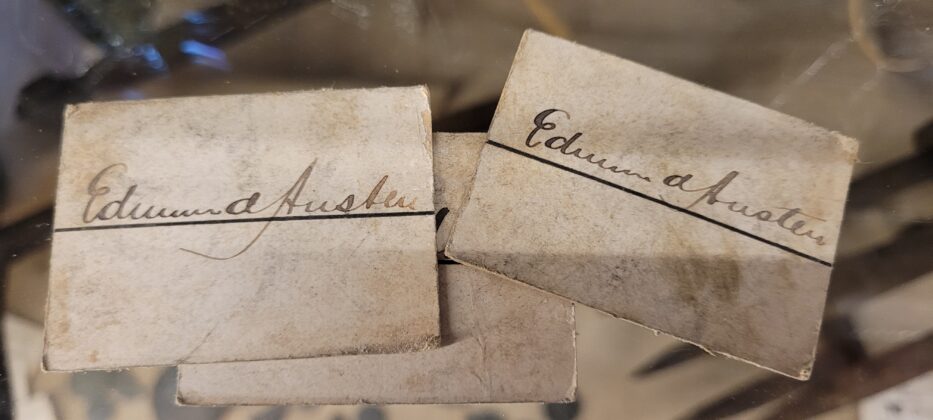

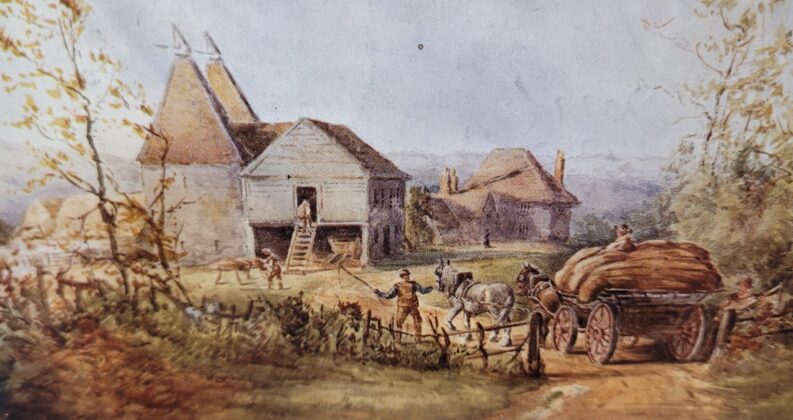

Hop farms grew up along the Rother valley with hop farming reaching its height in the 19th century. According to Leopold Vidler in A Numismatic History of Rye: “It is said that at one time you could walk out of Rye for ten miles without passing out of a hop field.” Jeremiah Smith, landowner and farmer, politician and a mayor of Rye, once farmed one of the largest areas of hops in England. Other hop growers included John Barnes at Cadborough Farm in the mid-18th century, and Samuel Selmes and Edward Barrett Curteis at Leasam Farm in around the mid 1800s. At Watlands Farm, Charles Skinner and his son, George, grew hops and on display in the museum in East Street are hop tokens and card from, amongst others in the collection, Edmund Austen’s farm in Brede, Thomas Austen in Udimore and Lawrence Reeve at Billingham Farm, Udimore. At one time Guinness owned 1182 acres of farmland between Ewhurst and Bodiam with 10 oasts and 50 kilns but by 1976 they had gone.

Sally says: “My interest in hop picking stems from my grandmother saying that, as a child, she came to Kent to help pick the hops. She was born in 1901 in Deptford, south-east London to a working-class family and was very much a city person. Unfortunately, I failed to ask her the details about her experience of hop picking but do remember her saying that she didn’t enjoy it! I think there can sometimes be a romantic view of hop picking but should imagine it was hard work in often uncomfortable conditions.”

Jobs on the hop farm

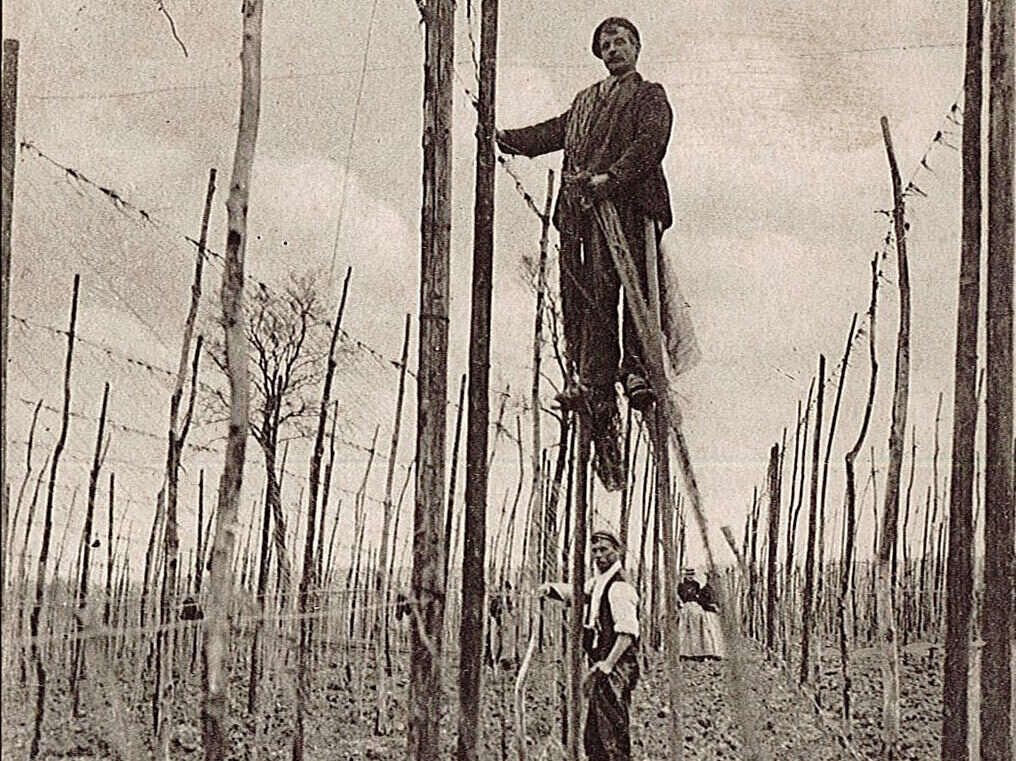

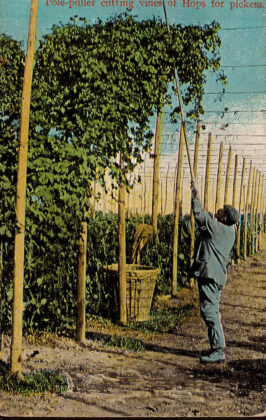

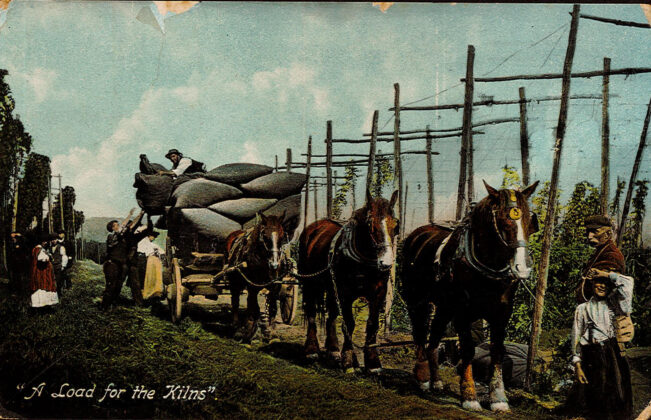

The growing of hops was labour intensive especially prior to mechanisation. Tall poles were put into the ground and men on stilts were used to erect and maintain wires and string that were strung up and across the poles for the bines (as hop vines are called) to grow along. Stilts were also used to tie the bines to the string in spring and used again in August and September when the bines were cut ready for the hops flowers to be picked and sent to the kilns for drying.

After picking, the hops were spread on cloth to dry above a fire which stopped the crop becoming spoiled by mildew and the most skilled worker on the farm was the dryer who needed to keep the drying even and at the correct temperature. Kilns were in in existence from the 16th century but the distinctive Kent and Sussex round oast houses replaced the square-shaped in the mid 19th century to avoid corners which, it was believed, could result in uneven drying. Today oast houses can still be seen around Rye in Playden, Cadborough Farm, and Hare Farm in Brede.

In addition to the pickers, workers were needed to plough, manure, weed, plant, prune and spray all year round. Other trades such as blacksmiths and carters, and later mechanics, who were needed to maintain tractors, ploughs, sprayers, were ensured work in areas where hop farms grew.

The rise of the migrant workers

Until the 1800s most hop pickers were local workers, Romany gypsies or other migrant workers. As demand grew in the 19th century, each year many families (up to 200,000 at its height) travelled from the East End of London, and other large cities, to pick hops, giving people a break from city life.

As Sally Master’s grandmother attested, it was far from a holiday: working on the hop farm was hard work. Men, women and children would be employed to cut the bines, strip the leaves after cutting and hand pick the hops flowers into baskets or sacks. The workers were paid according to how much they had collected. For each bin or basket that was filled the picker would be given tokens or notches marked on their tally sticks by the tally man.

Hop tokens were also used to pay the pickers because of the shortage of small coins. Many growers issued their own hop tokens, often designed with images, which workers could use in local shops or exchange for money at the end of the season.

Conditions were often very poor: the workers lived in run-down huts, barns, tents and stables with little access to washing facilities. Diseases such as cholera and smallpox were rife due to overcrowding and poor sanitation: cholera killed 43 hop pickers on one farm in 1849. However, conditions improved after the Society for Employment and Improved Lodgings for Hop Pickers was formed in 1866, with farms building timber or brick “hopper huts”. By 1870, special trains ran to bring families from east London to Kent and Sussex and often families went to the same farm year after year.

Even so, hours were long and the work poorly paid. When George Orwell went hop picking in 1931, he stated that “no worse employment exists”, and descriptions of the hop harvest appear in his book A Clergyman’s Daughter and also in W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage.

By the 1950s machines took over much of the work previously done by hand and large numbers of migrant workers were no longer needed.

The hop industry has declined dramatically since its heyday and there are now as few as 50 hop growers in the country. Tibbs Farm in Udimore continues to grow hops and offers tours of the hop gardens, the picking machine and oast house.

With the growth in the popularity of craft beers produced by microbreweries, let’s hope that the growing of hops in the area will continue into the future.

As well as the stilts, the museum at its East Street site has a display of Rye Pottery hop-ware, Victorian postcards showing hop picking scenes, hop tokens, and farming equipment.

Museum opening hours

The Rye Castle Museum has two sites, one in a former bottling factory in East Street and the other at the Castle / Ypres Tower.

Castle / Ypres Tower is open daily throughout the year. March 30 to October 31 from 10:30am to 5pm. November 1 to March 29 from 10:30am to 3:30pm.

East Street is open at weekends from April to October from 10:30am to 4:30pm (subject to availability of volunteers).

Image Credits: Rye Castle Museum .

I think I look forward to these articles more than any in RN, Juliet! Thank you. Hop fields used to exist behind our house, and though long gone, a bine appears every year. Not sure what variety it is… Anyway, keep them coming!! The Castle and the East St site are superb. Took my little boy to marvel at the longbows last week. (Winchelsea Museum is also brilliant, by the way!)

Thank you! I love researching and writing them. It would be fascinating to find out more about your hop bine!

I loved reading this, thank you. I have photos of my Mother, Grandmother and Great Grandmother picking hops in Northiam and have hops growing in my garden which were cuttings from the hops my Grandmother grew in her garden in Northiam.

How lovely to have that cutting and those memories.

Fantastic exhibit, which every ale lover should go see