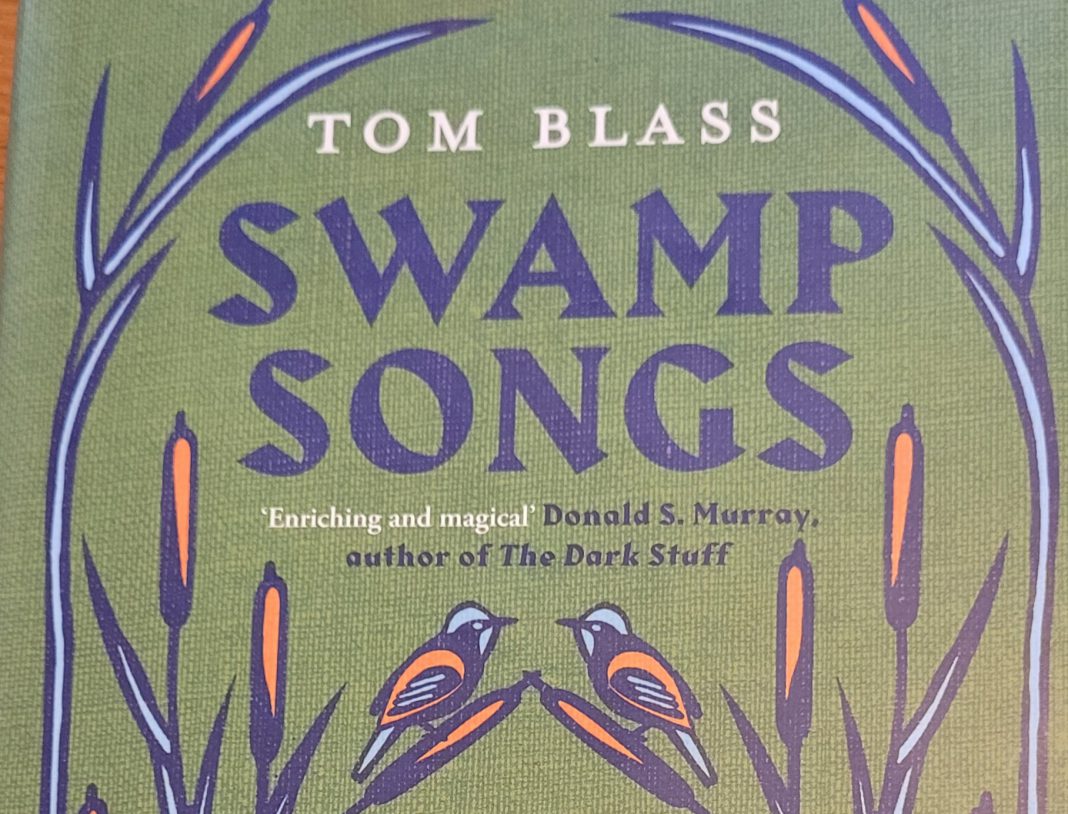

In his latest book Swamp Songs – Journeys through marsh, meadow and other wetlands, journalist Tom Blass explores the ecology and way of life found in some of the wetlands, swamps and marshes around the world. Frequently considered places of sinister mists (think of the monster Grendel in Beowulf and the setting of The Woman in Black), disease (the ague and “bad air” – mal aria), lawlessness (smuggling on Romney Marsh, the rebellion of the Marsh Arabs against Saddam Hussein) and separation from “civilisation”, people have continually worked to tame these damp places and their inhabitants. The negative connotations even make their way into the feverish rantings of Trumpian politics with his “Drain the Swamp” chants.

From Romney Marsh to the swamps of North Carolina, from Lapland to the Danube Delta and the Bay of Bengal, Tom Blass examines the constant struggle between man and nature, between the land and water – the intertwined relationship between the landscape, the flora and fauna, and the people that live in it.

“The world, according to the best geographers, is divided into Europe, Asia, Africa, America and Romney Marsh,” so writes Thomas Ingoldsby in 1837 in The Ingoldsby Legends. Echoing this sentiment was the writer Malcolm Saville, whose evocative descriptions of Rye and Romney Marsh vividly captured its atmosphere, and who referred to it as “the fifth quarter of the world”.

Perhaps in recognition of the fifth continent, or because he lives in Hastings, Tom Blass includes several chapters on Romney Marsh, giving the reader a glimpse of the characters that help shape it – the sheep farmers, the water bailiff, competitors in a tractor ploughing competition, the Lords of the Level, Jurats and chief clerk of the Corporation, and the environmentalists who work to protect it.

There is a certain ambivalence that the author feels towards Romney Marsh, describing its “dull, wet fields and ditches…For it boasts no quick-beating heart and few vital organs and even fails against an (unscientific) suite of criteria which one may measure ‘marshiness’”.

The Marsh, he writes, “…doesn’t shout about itself” and he lists the features that have “…turned back to the soil, the sky and the sea, affecting a kind of invisibility, as if hurrying to be forgotten”. And yet, he is drawn to it, like many others who love its sense of desolation, wide open expanses of grass, sea and sky, and its quietness: “…it is a favourite place for long and contemplative walks, for sounding things out in one’s head undisturbed by superfluous accoutrements of scenic beauty.”

For those not familiar with the history of the formation of the Marsh as we know it today, there are interesting sections on the building of the sea wall, the inning of the Marsh and the building of the Royal Military Canal (known as Pitt’s Ditch because of William Pitt the Younger’s orders to build it). The scourge of malaria is starkly conveyed through shocking statistics: between 1712 and 1742 over a quarter, and in some years over a half, of recorded deaths were from the “ague”; life expectancy on the Marsh in the 16th to 18th centuries was 25-30 years but rose to 50-60 on the mosquito-free hills above.

Further chapters describe the changing use of the Marsh: from mainly pasture to the now 90% that is arable; the effect of the second world war on the landscape; the building and de-commissioning of Dungeness power station; and the rather shocking proposal, made in 2012 and thankfully rejected, to build a nuclear research and disposal facility on the Marsh.

As a place well-known for its history of smuggling, Blass is quick to dispel the romantic image of the “owlers” and proto-Libertarianism of the “free traders” outwitting the intervention of the King’s taxes (Adam Smith saw smuggling as a good example of free market economics in action), describing in gory detail, the violence of the gangs in the pursuit of their trade. Blass points out that it is hard to ignore the parallels with today’s drug or people smugglers nor with the suspicion and hostility shown by some, towards present-day refugees arriving from across the Channel, akin to the treatment that French Huguenots received when fleeing persecution in France.

The bayous, levees and swamps of Louisiana, the reindeer-herding pastures of the Finnish swamps, the marsh and flood plain of a glacier-fed Icelandic estuary, or the mangrove swamps and forested islands of the Ganges-Brahmaputra estuary are not, on the surface comparable but, as the author says: “Look harder, and points of convergence come into focus. Such places, ‘fen-sucked’, frustrating, boggy, baggy, bedevilled by fever and ague…rebuff and are rebuffed by ‘normal’ society and its plodding agglomerations, and thus become attractive to, or at least last resorts for, outcasts, misfits and escapees. And, or, safe spaces for smuggling, banditry, or insurrection.”

This may not be how we see ourselves or Romney Marsh these days but through the people that Tom Blass encounters in his journeys – their lives, stories and myths – we can see how the peoples of the marsh, swamp and wetlands have adapted their environments and are, in turn, shaped by them too.

Swamp Songs – Journeys through marsh, meadow and other wetlands by Tom Blass is published by Bloomsbury.

Image Credits: Bloomsbury Publishing / Emma Ewbank .