This month’s museum object is the the longbow on display in Rye Castle Museum at Ypres Tower, chosen by museum visitor, nine-year-old Rex Harris.

The English longbow became one of the most feared and effective weapons from the 13th to 16th centuries and was the most important long-range weapon used at Rye Castle until 1457 when cannons were installed at the Gun Garden.

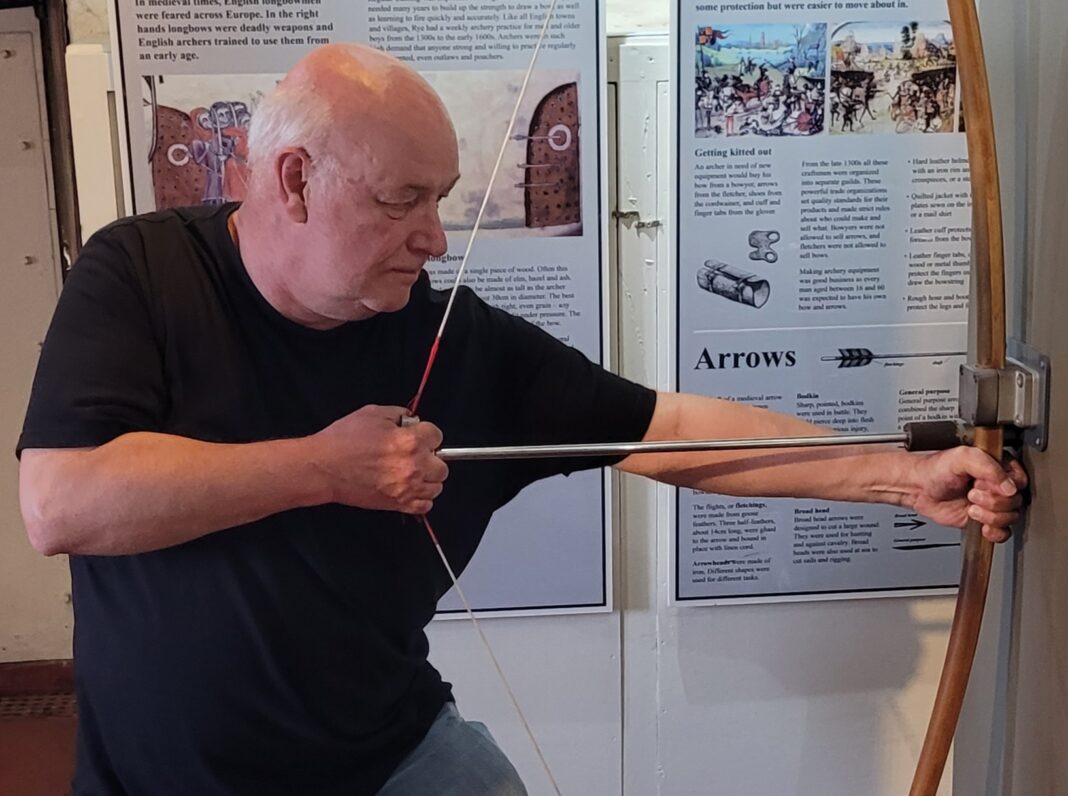

Alongside other weapons, a demonstration longbow at Ypres Tower can be pulled to see how much strength is needed to draw it. The bow is weighted at 105 lbs (48kg) which is the strength of the pull used in battles.

After trying the bow out at the museum, Rex was impressed by the ability of the archers: “I thought it was fantastic how they were so strong and could pull back the heavy bow and fire arrows through armour.”

The English longbow’s first recorded use was in South Wales in 1188, during a battle between the English and Welsh. An English knight named William De Braose claimed an arrow “had penetrated his chain mail and clothing, passed through his thigh and saddle and finally entered his horse.”

Archers would indeed have had impressive upper body strength, having trained from an early age. Hugh Latimer describes how boys and men were trained during the reign of Henry VII:

“My yeoman father taught me how to draw, how to lay my body in my bow … not to draw with strength of arms as divers other nations do … I had my bows bought me according to my age and strength, as I increased in them, so my bows were made bigger and bigger. For men shall never shoot well unless they be brought up to it.”

Archers’ skeletons recovered from the Mary Rose show the left arms and right fingers had enlarged bones and other deformations from the repeated drawing of the bows.

Bows had been used since Neolithic times for hunting and warfare, but it was the Welsh who first developed the longbow as a deadly weapon during the Anglo-Norman invasion of Wales in the 12th century, inflicting heavy losses on the invading armies. Due to the accuracy and range of the bows and the skills of the Welsh archers, they were conscripted into the English army by Edward I (1272-1307) for his campaign against the Scots. Indeed, Edward I was so keen on the longbow, that he banned all sports except archery on a Sunday to ensure that the use of the longbow was practised. This ensured a good supply of skilled and strong men who could be raised quickly into the army when needed.

Longbows were predominantly constructed from yew wood (although ash, hazel or elm were also used) which has high compressive strength, light weight, and good elasticity. The wood was dried for two years, while being shaped into a D. The stave of the bow was formed from half a branch with the heartwood (wood at the centre) resisting compression and the sapwood (outer layer) resisting tension. The length varied from four to six feet. Very few Medieval longbows have survived but a large selection of bows and arrows were found on the Mary Rose and ranged from 6ft 2in (1.87m) to 6 ft 11in (1.98m). The bowstring was traditionally made of linen, flax, hemp or silk fibres. They stretch when they get wet so had to be kept dry. In wet weather, an archer kept the string “under his hat”.

It was during the reign of Edward III, that the English longbow became the most famous weapon in the medieval period and for good reason – the English used them to astonishingly destructive effect during the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) against the French. Detailed records from the battles of Crecy (1346), Poitiers (1356) and Agincourt (1415), established the English longbow’s legendary reputation. Many thousands of archers gathered around Rye and passed through Winchelsea on the way to France.

In battle, the English massed their archers who released a cloud of arrows that could decimate soldiers and armoured knights. English archers could shoot more arrows per minute than crossbowmen. A skilled archer could release up to 20 aimed arrows a minute, but only for a short time before becoming exhausted. Archers were given two sheaves of arrows with 60-72 arrows in each, per campaign. To be able to shoot more quickly, they placed their arrows in the ground in front of them. Arrows had a long range, giving the outnumbered English an advantage over the French. At Agincourt, 5,000 archers fired 10-12 arrows per minute for the 7 minutes it took the French to advance up the hill, resulting in carnage – no wonder the English army was so feared.

English archers were so good because they were well-practised. Every male from the ages of 16 to 60 was made, by law, to practice archery at the Butts field (the straw targets were known as butts), that most towns or villages had. Rye’s two-acre Butt field lies behind St Michael’s Church in Playden, accessible through the churchyard. It was given to the people of Playden for archery practice and then for recreation and sport. A deed was established in 1703, today managed by trustees, and at present is used for grazing.

From the mid-14th century, England began to suffer from a shortage of yew to make the bow staves and so a Statute of Westminster, passed in 1470, ordered each ship trading in English ports to pay four bow staves for each ton of goods imported, which was later expanded to ten per ton.

The longbow dominated until the introduction of the use of firearms in battle. Despite having a lower rate of fire, guns and muskets required less training so armies could be raised more quickly. However, longbows continued to be used during the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487), the Battle of Flodden (1513) and the Kent militia had 1,662 archers prepared for the invasion of the Spanish Armada in 1588. They were even used in 1588 during a battle in Bridgenorth in the English Civil War.

Today, archery clubs around the country continue to use the longbow including in Rye – the Order of Rye Longbow (formerly the Order of Rye Longbowmen), has continued, shooting, until recently, at Leasam Farm.

Image Credits: Juliet Duff , Juliet Duff/Rye Castle Museum , The British Library MS 42130 f.147v http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_42130_f147v https://www.bl.uk/help/how-to-reuse-images-of-unpublished-manuscripts#, N Chadwick https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125037025 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en, By Andrew Kuznetsov – https://www.flickr.com/photos/-cavin-/3242603684/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=93568173 https://www.flickr.com/photos/-cavin-/3242603684/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en.

It is not true as a general statement that the archers were massed for battle. That might be so, but they were used exactly as modern artillery is used – both mobile and static. We know that around the battle of Crecy a mounted archer was paid 6d per day, a foot archer 3d. They might be massed but, again, we know that archers and foot soldiers were often used together, as they gave mutual protection when mingled. The longbow certainly “fired” at several times the rate of a crossbow, though the latter was more destructive. Both could penetrate armour.

I think the battle of Bridgnorth must have been in the 1640s (“English” Civil War), not 1588. A typo?

It’s said the Duke of Wellington seriously considered, but rejected, the use of archers in the Napoleonic Wars. A musket could fire only five times per minute in parade ground conditions, but required little training, as the article notes.

Terrific article, Juliet! Is the Order of Rye Longbow now in abeyance? Would seem worthy of revival, if so. (Especially with the army now down to 70k!)

Interesting reference to Leasam Farm too, in terms of its connection with local militia or reserve forces, as I think it was also connected to the clandestine work of the Home Guard Auxiliary Units in WW2 – the ‘Aux Units’.

A military crossbow could fire at best two bolts per minute and at worst one bolt every two minutes. This was because the bowstring had to be wound back with a windlass. Thus the heavier weight and penetration of a bolt was substantially outweighed by the longbow’s rapid rate of fire, and crossbows also had a shorter effective range.