Micheal Montagu is a published author as well as being a former Rye resident and has written a series of articles for Rye News on subjects not always connected to Rye or the local area but on topics we thought you would enjoy nevertheless.

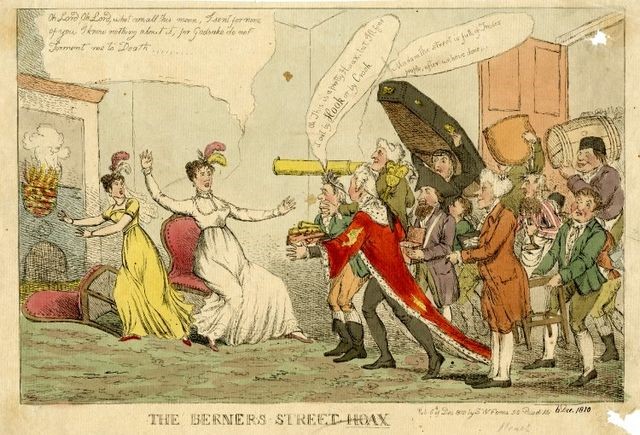

November 27th 1810 started like any other day in Berners Street, a quiet, respectable address, just off the north side of Oxford Street. It was described as ‘a quiet street, inhabited by well-to-do families living in a genteel way.’ At 5 AM, Mrs Tottenham’s (or possibly Tottingham’s) maid answered a knock on the area door at number 54. Outside she found a chimney sweep, who said that he had received a letter, asking him to take care of the chimneys. The maid was puzzled. No sweep had been ordered, and the man, perhaps a little disgruntled, went on his way. Another sweep arrived, then another; a dozen in all.

No sooner had the, by now harassed, maid seen off the sweeps there was another knock at the door. This time it was a man with a cartload of coal. After he had been sent on his way a cart full of furniture arrived. More sinister was to follow. There now arrived at the door a hearse, complete with an empty coffin and a string of mourning coaches to follow it. More was to follow, causing the poor widow and her maid to hide in abject terror.

Greengrocers arrived with barrows full of fruit and vegetables. Fishmongers and butchers arrived with quantities of their wares. To wash them down was the stock of wine and spirit merchants and brewers. Cakes, pastries and sweets arrived. Dentists had received letters summoning them to attend a patient, as had physicians. Then priests and clergy of more than one denomination. Lawyers arrived to write wills. Wig makers had been written to, as had tailors and shoemakers. Antique and curio dealers arrived, summoned to both buy and sell. Clockmakers arrived. So did hairdressers and opticians. Pianos arrived and then ‘six stout men carrying an organ.’ Domestic staff arrived unbidden; cooks, housemaids, footmen. Coachmakers brought elegant carriages. The quiet street was blocked by tradespeople, craftsmen and professionals, all summoned by letter to appear on 27th November.

Then it became even more interesting. High dignitaries began to arrive, again summoned by letter. A member of the Cabinet of Prime Minister Spencer Perceval arrived. The Lord Chief Justice, Lord Ellenborough arrived, as did Charles Manners-Sutton, Archbishop of Canterbury and the Governor of the Bank of England. Even more amazing was the arrival of the Commander in Chief of the British Army, His Royal Highness Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, a son of King George III and Queen Charlotte. Next to arrive was the Lord Mayor of London, again with a letter. The letter said that a lady in Berners Street had been called to attend the Lord Mayor’s Court in the Mansion House, but was too ill to comply. She would, it said, deem it a great favour if His Lordship would call upon her, so that she could make her deposition on oath. He quickly realised that everyone had been the victim of a massive hoax and went to Marlborough Street police station and reported what had happened.

By now Berners Street was blocked from end to end by furious professionals, tradespeople and important personages. People arrived to see what was happening and Berners Street, that quiet, respectable thoroughfare was ‘choked with vehicles, jammed and interlocked with one another.’ The chaos spread to adjoining streets and the area became gridlocked. The police were called but such was the crush that there was, in reality, very little they could do. A contemporary writer said that, ‘drivers were irritated……disappointed tradesmen were exasperated, and large crowds enjoyed the malicious fun.’ Pickpockets thought that the birthday of their lives had arrived and enriched themselves at the expense of others. Carts were turned over and their contents broken. Alcohol, intended for delivery, was widely indulged in by those who had been cheated, presumably enjoyed gratis. Meanwhile, the poor lady of the house and her staff were trapped and in terror. Those not inconvenienced were thoroughly enjoying themselves but, the ‘tangible material damage done was itself no joking matter.’ Satisfaction was demanded and those who had ‘suffered in person or in purse’ were determined to lay charges against the person responsible. That, it was clear, was not the, by now hysterical, Mrs Tottenham (or Tottingham.) Not until late in the evening did the throng begin to disperse. A reward was now offered to anyone who could name the culprit behind the chaos.

Had those who had their time wasted and goods damaged been aware, they could have caught the perpetrator red-handed, for he had spent the day watching the mayhem that was his creation from the window of a hired room across the road from number 54. Theodore Hook was a composer, writer and well-known player of pranks. He disliked the gentility and quiet of Berners Street, so bet his friend Samuel Beazley that ‘he could, in a single day, make Berners Street the most talked of place in London.’ Despite the best efforts to find him, Hook was never caught. He apparently thought it prudent to be ‘laid up for a week or two,’ after which he set off on his travels around England. His friend Beazley had to pay up the winnings for the bet. It was just one guinea!

Image Credits: Michael Montagu .