My mother Elizabeth, née Jermyn, was a GP. I knew she had graduated before World War 2 in physiology; that from 1939 she had been secretary to the famous geneticist JBS Haldane, and during the war had taken part, with Haldane’s research team, in diving experiments to test the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus, or DSEA, an oxygen rebreathing device designed to aid underwater escape from submarines. Haldane had initially been enlisted by the Admiralty following the loss of HMS Thetis, a submarine which sank in June 1939 in the Mersey estuary after a failed dive test, with the loss of 90 lives.

I always suspected that her appointment as his secretary was partly because at that time she, like Haldane, was an ardent communist. The team was based at University College, London, until bombing raids forced its evacuation to Harpenden, where it found a new home in the agricultural research establishment, Rothamsted.

The diving experiments (of which there were several hundred) were conducted in London by Haldane’s research group of civilians at the headquarters of Siebe Gorman, which had pressurised chambers that could simulate underwater deep dives. When the facility in Lambeth was bombed out it relocated to Teddington. The entire team, Haldane included, took part in the experiments. These were fraught with risks. Getting “the bends” was frequent; loss of consciousness occurred during several experiments, so each subject was accompanied by another team member both to observe and to raise the alarm if something went wrong.

During one such, my mother suffered a seizure underwater and fractured several vertebrae. Although she continued participating for a while she was eventually relegated to dry-land duties on medical advice.

That was all I knew. I now know that she had been rather economical with the truth. The DSEA was not itself being tested, but was being tried with different gas mixtures to ensure the safety both of midget submarine crew and of divers probing the underwater defences on the French coast prior to the invasion which would become known as D-Day. The work was not only dangerous but also top secret. Like so many who did secret work she never spoke of it.

Top secret documents can eventually see the light of day, and an American dive expert, Dr Rachel Lance, who had already written a book about the loss of a Confederate submarine in the American Civil War, uncovered them, including many experimental notes made by my mother. The results of her research appear in her new book “Chamber Divers: The Untold Story of the D-Day Scientists Who Changed Special Operations Forever”, to be released in the UK on June 6 – the anniversary of D-Day. Lance describes the rationale for the diving experiments, the team members who took part, the results and the outcome – a revision of the understanding of underwater gas mixtures, the application to midget submarine work and the D-Day landings and the machinations that led to the seminal work being claimed and published after the war by someone else. Lance explains how this came about in a story which reads like a thriller, which perhaps it is. And I learned things that I would never have known about my mother.

Breathing high concentration oxygen deep under water is now acknowledged to be highly dangerous. The proof came in the experiment during which my mother had her seizure. Prior to this the difference in effect under pressure when dry, and when underwater, had never been observed and the reason for the difference remains unclear to this day. Lance claims that the discovery enabled the success of D-Day and the later safe development of scuba diving.

Rothamsted was where mother met my father, and then decided to train as a doctor, going to medical school in the day and working for Haldane in the evenings and nights on a timetable of 132 hours per week. That’s another story. In later life she struggled with osteoporosis and bilateral hip arthritis, both almost certainly contributed to by her fractures and by suffering “the bends” more than once. She never complained. She was a very modest person and would I am sure be embarrassed by the fuss now surrounding her role in the work. I believe that she and Haldane’s team deserve the full recognition they never had for putting their lives and health at risk in the service of the country, so as she is no longer alive (she died in 2010 at the age of 94) I will make that claim on her and their behalf’s.

“Chamber Divers: The Untold Story of the D-Day Scientists Who Changed Special Operations Forever” by Rachel Lance is published in the UK by Bedford Square Publishers. Her previous book is “In the Waves: My Quest to Solve the Mystery of a Civil War Submarine” (2020). Both are available through Amazon and Waterstones.

For more on the local event’s to mark the 80th anniversary of D-Day click here

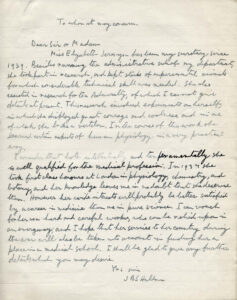

Image Credits: Andrew Bamji .